Going Inland Empire

Is there meaning to be found within Inland Empire?

If so, you must allow a decade between each viewing. That is the conclusion I have come to.

Along with: “Exterminate all rational thought” (thanks, Naked Lunch).

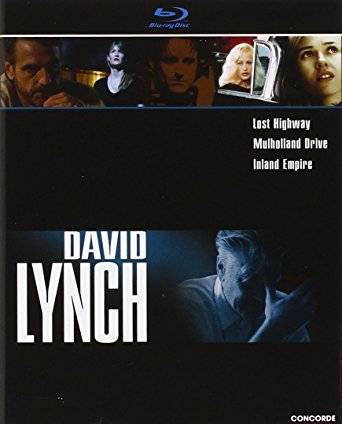

It’s a film by David Lynch – a man whose ambition is matched only by his ambiguousness, and whose fan base is matched only by those who view him as a quirky hack with an aversion to traditional narrative storytelling.

On my first go-‘round, I loathed Inland Empire, but kept it on my shelf with the tachyon knowledge that I’d be compelled to revisit it at some point.

A recent conversation with Billy Crash – coupled with a snow day that closed the office – provided an opportunity to do just that.

Inland Empire may not leave as potent a mark as, say, Eraserhead or The Elephant Man or Blue Velvet, but it’s a film that… remains, long after viewing.

Shot on consumer-grade digital video (a more experimental conceit in 2006), one of the constants of this Lynchian world is that it looks like shit. Early on, the camera setups feel clunky and inept. Daytime exteriors are abrasively bright, while dimly-lit rooms and sidewalks border on the indecipherable. The film frequently submits to the murk of total darkness. (The image-calibration option on the DVD – also present on Lynch’s initial disc release of Eraserhead – does little to help the overall aesthetic as it relates to the viewing experience.)

But… maybe the murk is the message.

Inland Empire is a hefty three hours of murk and fades-to-black that frequently made me think the movie was over. This phenomenon also occurred in the auteur’s pre-digital mindbender, Lost Highway.

Did Lynch create a movie that looks like shit – with many finer details obfuscated – as a challenge to the audience? Is it a test of the viewer’s tolerance for aesthetic ugliness? (Conversely, I can buy the cacophonic, discordant sound design, which has always been part of the director’s M.O., dating back to his short films.)

I consider myself a fair-weather Lynch fan. There are times when I find his work overrated, or little more than torture-tests designed to drive pseudo-intellectual film students crazy with analysis. A fan of Lynch might feel a contradictory mix of emotions toward Inland Empire’s daunting run time: at best, three hours of idiosyncratic weirdness could inspire rapturous sensory overload; a worst-case scenario could be a patience-testing slog.

Embracing the Murk

To a certain degree, Inland Empire exists in both categories. Its self-indulgence is undeniable, and the cannibalization of Lynch’s own Mulholland Drive obvious. When actor Devon Bark (Justin Theroux) states to director Kingsley Stewart (Jeremy Irons), “I didn’t know this was a remake – I would never do a remake,” it’s a self-aware rebuke to the critics making assumptions before the plot has properly unraveled. (Theroux played a young auteur in Mulholland; and Laura Dern’s Nikki Grace is comparable to Betty, the aspiring starlet Naomi Watts portrayed, in the same.)

Dern is seldom given roles that match her immense potential, so it stands to reason that Inland Empire is a macabre gift to the actress, who appears to essay several characters – or several sides to a single character, depending on your interpretation – over the course of the film. She’s introduced as Nikki, a slightly aloof actress (who could be an estranged sister to Maps to the Stars’ Havana Sagrand); is reincarnated as a passive, dissatisfied housewife; and, in her final form, a discombobulated prostitute named Susan Blue. Dern delivers a stunning, career-best performance here. The extended sequence in which Susan recounts her troubled personal history to an apathetic, bespectacled confessor (the God-figure of the piece, maybe?) is an intoxicating mix of jarring flashbacks, Noir lighting, and absurdly matter-of-fact dialog. She describes a violent encounter with a would-be rapist with a jadedness that suggests she’s long since abandoned a functional, “normal” existence.

Then there’s the seemingly peripheral themes of voyeurism and passive viewership, and how they play into the plot at large. Inland Empire is bookended, sort of, by a Lost Girl (Karolina Gruszka) watching the events of the film/dream unfold on a turn-of-the-century television, her cheeks streaked with tears (of sorrow or rapture?). Is this character seated at the Oscars in some parallel universe, watching Dern accept Best Actress for the film-within-a-film (within a film, if you count the viewer viewing the Lost Girl and Dern)? Or are the tears inspired by the finiteness of experience – that what she is viewing has affected her so deeply, she never wants it to end? What of the non-sequitur-spouting trio of “rabbits” (human bodies with oversized rabbit heads), who exist within the context of a single-camera sitcom, reciting unfunny dialog that nonetheless gets emphatic laughs from an invisible studio audience? One of the rabbits (voiced by Scott Coffey) enters the sitcom set, only to exit into Real-World Poland.

To be continued…

The Plot Sickens: Don’t miss Jonny Numb’s review of 68 Kill!

Crash Analysis Support Team

Jonny Numb

Jonny Numb

(Aka Jonathan Weidler) has experienced enough pet and human death to justify several volumes of Pet Sematary fan fiction. He co-hosts THE LAST KNOCK horror podcast on iTunes, and can be found on Twitter and Letterboxd @JonnyNumb. In addition to Crash Palace Productions, he also contributes to Loud Green Bird.

(Still from Inland Empire via Alternate Ending.)