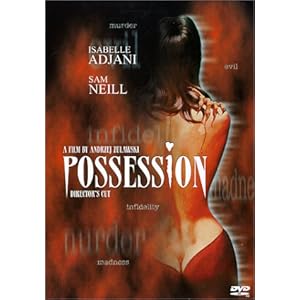

A wide-eyed, jaw-dropping, migraine of a trip

Husband and wife’s relationship collapses – as does everything else.

Writing about POSSESSION is akin to trying to deconstruct David Lynch’s mind trip ERASERHEAD (1977) or Takashi Miike’s bizarro VISITOR Q (Japan, 2001). And although director Andrzej Zalawski’s film is based upon the trials and tribulations of his own divorce, this doesn’t make things easier.

Isabelle Adjani’s (Anna/Helen) high-strung and destructive character wants nothing to do with her husband, Mark (Sam Neill), who wants to keep the marriage together at all costs – with an equal amount of hysteria and hostility. Both, however, seem to have only minimal concern over their son Bob’s (Michael Hogben) young life. At first, it seems Anna wants to run off and remain with the calculating yet emotionally bizarre Heinrich (Heinz Bennent), but that relationship is also doomed to fail in horrific ways.

Never in a movie has there been so much screaming and violence concerning the demise of a relationship. The action between husband and wife is so tumultuous, so loud and nasty, one sits shellshocked as the no-holds-barred story unravels, reconnects, falls apart, becomes seemingly tangential, and back again. Zalawski’s high-powered and emotionally driven film never apologies and it never bows to conventional storytelling. Instead, the audience is thrust into pure visceral mayhem with no hope of salvation.

In such a tale, one may find it hard to discern what one bears witness to. On the one hand, we have a couple looking for their respective, ideal partners, and work to reconstruct each other. Mark finds schoolteacher Helen, his wife’s doppelganger, to love and embrace, while Anna recreates Mark from the equivalent of primordial ooze. Both clearly enjoy the superficial appearance of their mate and their creations, but what lies beneath is in need of retooling. However, neither is God, a question that comes up at several key moments in the story, therefore, what they have manufactured does not live up to their ideals. Both Anna and Mark are so hellbent on control, on indulging in one worldview, that neither is satisfied by the results.

Mark considers God to be a disease, and Heinrich thinks this notion allows people to get close to Him/Her/It, while Anna says, “What I miscarried there was sister Faith, and what was left is sister Chance. So I had to take care of my faith to protect it.” Faith to protect Chance or did she need Faith to protect her faith? Anna fails to realize that faith is like hope: a word of inaction where one waits for another entity, group or individual to take responsibility and save the day. Considering the concept of faith, Anna “hopes” something is there to protect her, and she never comes to terms that she’s a daredevil without a metaphysical safety net – there is no God for her because Anna never realizes that she is in fact her own god, and a savage one at that. Due to this lack of understanding, and due to not grasping the role she plays in her own existence, Anna runs amok and destroys the world around her. The mentioning of God is used sparingly in the film, yet remains poignant. It’s as if Mark, Heinrich and Anna want to know if a higher power is watching the annihilation they cause so they can avoid punishment. If not, they will then be allowed to pillage and plunder with abandon since no one is watching – as they swipe cookies from the jar and smash it in the process. If they are each their own gods, they cannot be held accountable for their actions since they have executive privilege. Free of prosecution from above, they collectively spiral out of control and cry havoc.

Yet, there’s more to the story than mere relationships, self-assessment and the questioning of God. As the film evolves, Zalawski attacks the notion of “us versus them”. The story takes place in West Berlin during the Cold War where West and East Germany represent the horror of a coming world conflict between two superpowers. Mark is British, Anna is German, and never the twain shall meet. Even as they recreate the other persona, the replicant for each to love and grow old with, it doesn’t work. For the persistence of control over that “other” remains supreme, which leads to more conflict and destruction on a much grander scale as the “others” flex their own will and self-determination. Even young Bob knows a union is impossible and takes his life into his own hands.

Another example of a failed union is the case of Heinrich. He’s indicative of a western lifestyle that can’t come to terms with the notion of self. As a man, he lives with his mother (Johanna Hofer), who puts clean sheets on his bed, yet seems independent and worldly, as if he doesn’t realize he’s fooling himself. Even in his darkest hour, he pleads with his nemesis, Mark, for help because he has become impotent. His entire life has been a façade, a joke like an American politician during the Red Scare who talks tough but cries in the corner alone for fear of an invasion that will never come. His counterparts are the West German agents Mark works for. They are cool, smarmy and feel they can wrangle in anyone outside of their sphere of influence because they are the secret manifestation of the state with all the connections and weapons political power can buy. They’re simply a gang that fails to see that suddenly anarchist Mark doesn’t give a damn and will fight anyone in the way of his rage – his own war for control of self and those closest to him. If Heinrich is the emotional wreck, and the agents the arrogance of control, then Helen is the deer in the headlights who thinks love and kindness will solve every problem. It won’t.

In the heart of humankind, though many may hope for peace and love, the threat of disagreement will always lead to conflict. Maybe this is what Zalawski wants us to understand. There is no such thing as a perfect relationship – a perfect marriage. Once we grasp that idea, and embrace that we’re all searching for someone who isn’t exemplary, but close enough, we may be able to find some semblance of happiness, some truce to quell internal and external warfare. Mark and Anna want utopia, but this is as impossible as it is implausible. Utopia may only exist if there is but one person left on Earth. Even one additional person will in some way differ with the other, and conflict will ensue. Husband and wife chased a definition for a perfect life that could never possibly exist, and when they failed to live up to society’s denotation, they fell apart.

The acting is fantastic, and lovely Adjani (who also starred in Roman Polanski’s wonderful THE TENANT (France, 1976) as well as many other notable films), stands out as a woman who has become undone and psychotic. Sam Neill also shines as the man who may morph into the Joker if he slashes into his smile. Even so, Bennent’s performance as the enigmatic lover is one for the ages. Bruno Nuttyen’s cinematography keeps us in the isolated fight between hungry caged tigers, and Carlo Rimbaldi’s special effects certainly hold up thirty years later in very disturbing ways.

POSSESSION is a movie for the viewer who embraces it and finds their own themes and messages among the scraps and milieu. After all, the haphazard nature of the film mirrors the twisted and disintegrating mindset of its characters. Sit back, indulge and come to your own conclusion with a movie you will find difficult to ever shake from your mind.

4.5 out of 5 stars